A God, A Pirate and the Birth of a New Urban Religion in the Deccan

The Ayyappa Temple at Sabarimala is an extremely popular one. Located in the Periyar Tiger Reserve in Kerala’s Pathanamthitta district, it has also been the subject of much controversy on account of its rule disallowing women between the ages of 10 and 50 from entering the temple.

The pilgrimage to the temple is unremarkable for the most part. At first sight, there are many seemingly unusual rules that are required to be followed before one embarks on it – a fast that one keeps over 41 days, a bead necklace to be worn at all times, food restrictions, a certain colour scheme as far as clothes are concerned (black, blue or saffron), no footwear (in preparation for the barefoot trek to the top of the hill where the temple is located) and so on. But arguably, there are likely other such comparable pilgrimages with rules and observances.

It is in the actual journey that its most interesting aspect is visible. By all accounts, a stopover at Vavar Mosque/dargah at Erumeli in Pathanamthitta, is de rigueur before the temple visit. Thousands of Telugu pilgrims coming from places in far away Andhra Pradesh stop here singing Hindu devotionals liberally mixed with kalmas from the Quran in Telugu dedicated to Vavar Swamy. How had this come to be? What could have resulted in the birth of this tradition?

Vavar Mosque. Photo: Dinesh Valke/CC BY-SA 2.0

Given that Sabarimala is in Kerala, a step or two removed from the Deccan heartland, tracing the origins of this tradition leads to the realisation that this story was not an outcome of the land route, which is how much of the Deccan engaged with Islam. Instead, it is traceable to the ancient connections that the Malabar coast enjoyed with the Arabian Peninsula. But cultural regions are not air tight containers. Their boundaries are not strictly policed. Stories, objects, songs, images are smuggled across boundaries all the time. Places get networked and connected and the histories of how these came to be is often lost in time. Vavar mosque at Erumeli is a meeting point for the many layered histories of the Deccan and the areas adjoining it and their interaction with the regions beyond the Indian subcontinent.

Exploring the mythology

Erumely is home to the Vavarswami Palli, named for Vavar, Ayyappan’s Muslim companion.

Who was Vavar? There are many strands to this story.

Vavar was Ayyappan’s companion – that much is common to all stories. But what were the circumstances in which this friendship was cemented?

The mythological story of Ayyappan revolves around his birth from the union of Shiva and Mohini, his miraculous discovery as a baby in the forest by the childless ruler of Pandalam, his adoption, his extraordinary abilities and his detour to the forest at age sixteen in dubious circumstances when the queen and a wily Dewan conspired to do away with the adopted Ayyappan to ensure the enthronement of the queen’s natural-born son. From the forest, Ayyappan was instructed to bring back the milk of a lactating tigress – a cruel errand intended to ensure his death.

But then, Ayyappan, of divine stock as he was, much to the chagrin of the queen and the Dewan, returned to the kingdom riding the tigress and with the required milk. Upon his return, Ayyappan’s divine provenance was also revealed to the king. Subsequently, Ayyappan renounced the world and a shrine was built for him at Sabarimala.

“Ayyappa Swamy” bazaar art, c.1950s. Source: eBay, June 2012

In the medieval period, the Ayyappan legend expanded. He also came to be regarded as a deity who protected traders and merchants from outlaws and brigands. In this capacity, he came to clash with Vavar, who was a pirate looting and plundering along the Kerala coastline. Some maintain that Vavar was originally ‘Babar’ and the variation in his name owes something to the language of the region. Ayyappan defeated him following which Vavar underwent a change of heart and began to help Ayyappan in protecting the travellers. In a sort of extension to this story, together they outwitted the outlaw, Udyanam and ensured the safety of trading caravans.

In another variation, Vavar happened to be in the area and Ayyappan accepted his help to defeat the outlaws. But what exactly was Vavar doing in the region? He apparently was a Muslim saint/teacher who came to the region to spread Islam and joined forces with Ayyappan. In time, he came to be revered and given the existing reverence for Ayyappan, was co-opted into his legend.

In yet another telling, through which Ayyappan was incorporated into the pantheon of demon-slaying Hindu warrior gods and goddesses, he slays the demon princess Mahishi at Erumely (Durga slays Mahishashura). Vavar assists him in this endeavour. Mission accomplished, when Ayyappa leaves for Sabarimala, he asks Vavar to stay put at Erumeli. He also tells his devotees that whenever they wanted to see him at Sabarimala, they should first visit Vavar.

One legend identifies Vavar as having belonged to Pandya Desam near Madurai whose family migrated to the Travancore region to escape an attack by a Pandyan minister. There, the family encountered Ayyappan and the friendship began. There are no details of Vavar’s origins or background. This is the only legend that connects the Vavar tale with the Deccan proper. All other stories are of coastal origin and hark back to the sea connection with Arabia.

File photo of devotees inside the premises of the Sabarimala temple in Pathanamthitta district in Kerala. Photo: Reuters/Sivaram V/File Photo

Excavating the history

From the days of the Classical Roman Empire (first century BCE to second century CE), merchant mariners from the Eastern Mediterranean frequented the Kerala coast to trade in spices. This was also the period when Muziris (near modern-day Kodungalloor) as a port seems to have been a significant stopover in seaborne world trade, even meriting mention in the Greek travel text, Periplus of the Erythraean Sea. Roman presence in the Kerala region seems to have continued till the fourth century CE when with the decline of the Roman Empire, it gradually ceased.

Scholars date the extension of the Ayyappan legend to becoming a merchant-protecting deity to between the 1st and 3rd century CE, a likely outcome of the many threats that seaborne trade faced at that time. Appealing for divine intervention was perhaps not unusual and appealing to a god already popular in the region very understandable, therefore.

Vavar’s incorporation into the Ayyappan legend is likely to have taken place post the seventh century CE when post the birth and growth of Islam, the Arabs resumed their trade with Kerala which had dropped off along with the Romans about three centuries earlier. Given the documented presence of Arab Muslims in the region almost contemporaneously with the birth of Islam and the subsequent growth of this trade, Vavar’s emergence is easily understood. It was a blending of two traditions which was natural for that time, and which seems to have continued in unbroken fashion ever since.

Until the 1960s, the pilgrimage actually began at Erumely where the route went through forests and steep hills. Groups of devotees sung songs along the way in order to keep up their morale and display their devotion. With the Sabarimala pilgrimage becoming wildly popular, the old route is rarely used. Roads now lead to the foot of the hill, where the shrine is located. But despite that, pilgrims make the Erumely shrine stopover on their way to the temple. It is a matter of routine…and faith!

Beginning in the 1970s and picking up pace in the 1980s, the Ayyappa rituals began to travel to many other places hundreds of miles away from Sabarimala – mainly urban centres in erstwhile Andhra Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka and to lesser extent in Maharashtra. Devotees in all these places follow a rigorous 40 day ritual dressing and maintaining abstinence and traveling on foot to witness the celestial festive events in Sabarimala surrounding the uttarayan (or the northward movement of the sun in relation to the earth). But what keeps the fervour in these places is ritual group singing – bhajans. The widespread availability of cassette tape players in the 1970s and 1980, particularly with devotional songs sung by the immensely popular Jesudas contributed to this growth.

Nothing demonstrates the enduring power of Vavar legend than the fact that today hundreds of small Ayyappa shrines emerge across towns of erstwhile Andhra Pradesh and in many of these places devotees sing songs in praise of the friendship between Vavar and Ayyappa in local languages. Centuries in the making, the story of the Ayyapan-Vavar friendship continues to hold firm and gestures to syncretic presents that we inhabit to this day.

This article first appeared in The Wire as part of the Many Worlds of the Deccan.

Related Articles

Has Rap Found its Home in the Deccan?

The Deccan is a place of unlikely arrivals and departures – cultural practices from every possible region of the world have found home here and gotten reinterpreted and gifted back to other regions. One such recent arrival is hip hop from Black and Hispanic...

The After-Lives of Historical Figures in the ‘Pan-Indian’ Telugu Film

Contemporary film history of the Telugu people has at least one instance of a hyper masculine superhuman celluloid figure that appears time after time to establish territorial order: Alluri Sitarama Raju. The source for this celluloid figure was the leader of what...

Telugu Modernity and the Curious Case of Enlightened Privilege

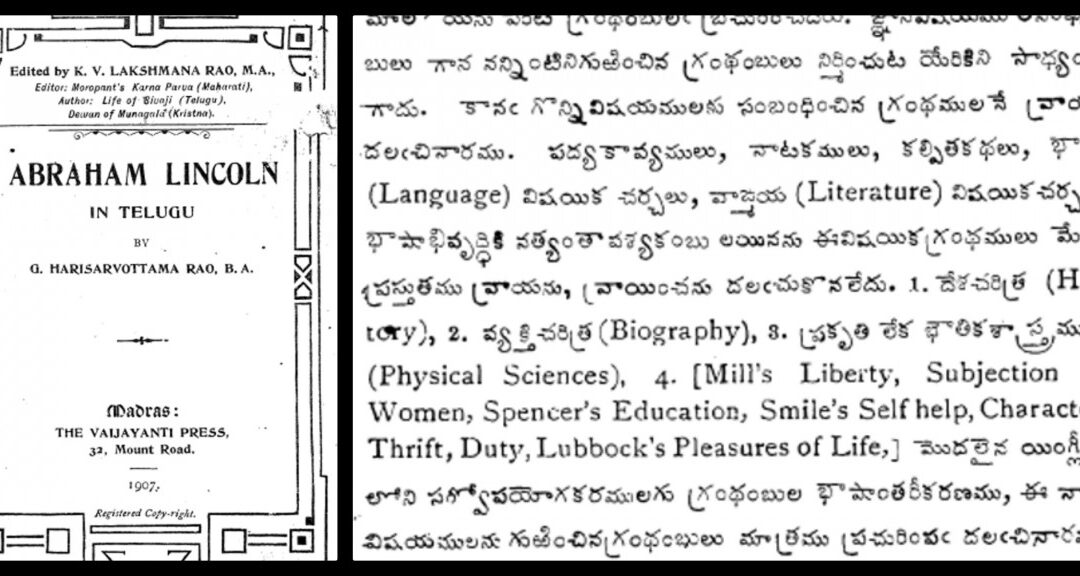

In 1907, Vijnana Chandrika Mandali, a Telugu publishing house, began their operations with the goal to ‘improve Telugu literature’.

The Mulki and the Mulk: How Belonging Is Layered in the Deccan

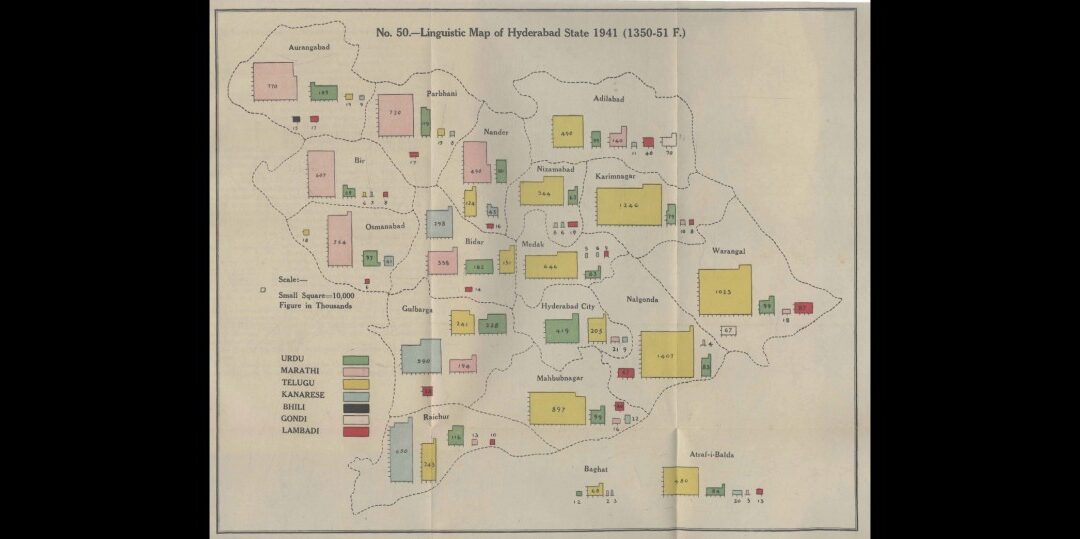

The categories of Mulki and non-Mulki began to appear on the Hyderabadi political scene from the mid-19th century onwards as a response to the influx of Urdu-speaking North Indians being recruited into the state administration.

The Uncanny Sisterhood of Deccan’s Languages

‘Pora khaalli? (Have the children eaten?)’ These are two utterances in Marathi spoken in Osmanabad and Solapur districts. But a speaker of Marathi from the central or western parts of Maharashtra may be perplexed at what is being asked of them. Is ‘Kaa karlaalaav’ the...

Deccani Identity: Instrumental Logic or Deep Love of Land?

The diverse ways in which the Deccani identity is invoked in textual sources and oral traditions indicate that newcomers to the Deccan adapted to the ways of the land, developed strong affinities to local landscapes, and adopted cultural practices and markers.

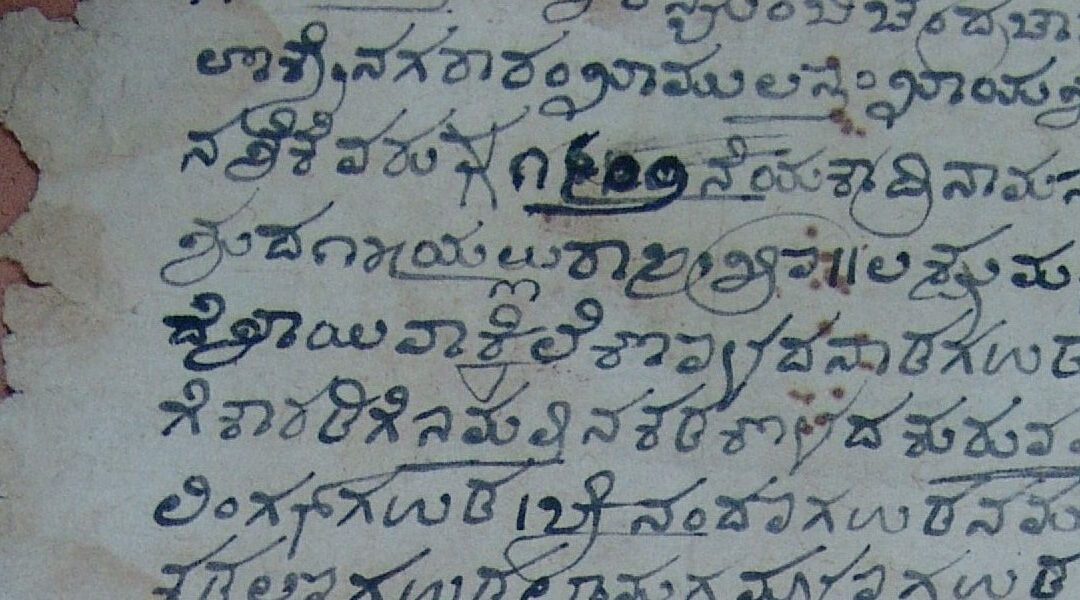

What an 18th-Century Sale Deed Reveals About Language and Territory in the Deccan

The documents hint at more give-and-take in the scribal environment than the one-way “imperial” narrative premised on modern mono-linguistic identities.

Afterword: Who does the Deccan belong to?

On September 17, 1948, more than a year after India became independent, the Hyderabad–Deccan state was integrated into the new Indian nation-state ruled from Delhi. This event, celebrated by some as “liberation,” set in motion decisive processes of integration,...

Rabindranath Tagore’s visit to Hyderabad: When poetry triumphed over politics

The September 17th anniversary of the ‘Police Action’, which led to the integration of the princely state of Hyderabad in 1948, has become increasingly contentious with selective use of history by political parties to further their current polarising agenda. Lost in...

Hyderabad’s distinct Chaush community has roots in Yemen

At a time when Muslims in India are constantly asked to display their nationalism and explain their choices of food, love and profession, it is important to remember that identity is not a monolith. It is historically constructed and multidimensional. Neither can it...