Hyderabad’s distinct Chaush community has roots in Yemen

At a time when Muslims in India are constantly asked to display their nationalism and explain their choices of food, love and profession, it is important to remember that identity is not a monolith. It is historically constructed and multidimensional. Neither can it be restricted by visa and passport regimes on printed paper, nor can it be defined by legal definitions of nationalism and citizenship. It is lived everyday as memories and connections between multiple local, regional and universal contexts.

The Chaush, a distinct diasporic group in Hyderabad that has roots in the Hadramawt region of Yemen, exemplify the possibilities of inhabiting translocal identities, as this essay shows. Chaush is an Ottoman Turkish word that denotes a junior military rank indicating the predominance of soldiers and mercenaries in the early Hadrami migration to Hyderabad centuries ago, from Hadramawt valley or wadi in South Yemen. The scholars and traders of the wadi are subjects of legends and it occupies an important place in early Islamic history. Hadrami Arabs were instrumental in the spread of Islam in the Indian Ocean through complex networks of kinship and economic relationships along its port cities. Through centuries, Hadramis have travelled as religious scholars, traders and mercenaries. Their presence is still written across the Indian Ocean from Comoros Islands to Kerala to Singapore and Indonesia.

Most Hadrami Arabs came to Hyderabad to work as soldiers in the Nizam’s military, irregular forces, in private militias or as jamadars/tax collectors. They also occupied high ranking military positions as officers in the Hyderabad Army. For example, General El Edroos, a Hadrami, was the Commander-in-Chief of the Hyderabad forces when they surrendered to the Indian forces in 1948.

But, as scholars have noted, Arab mercenaries were already a part of the multiple armies, especially Maratha armies, across the Deccan before the British and the Mughal empires started competing for dominance. For example, the Gaikwad Maharaja of Baroda employed many Arab soldiers, including Ja‘far al-Kathiri, whose successors later came to work for the Nizam of Hyderabad and financed the Al Kathiri Sultanate in Hadramawt with the profits they earned in Hyderabad. Another prominent Hadrami family is the Al Quaiti family, a part of Hyderabad’s nobility, which established the important Al Quaiti Sultanate in Hadramawt.

In Hyderabad city, Barkas and Chandrayangutta are both predominantly Chaush neighbourhoods. Names of shops, hospitals and schools in these areas announce this community’s claim on this space. Restaurants serving Mandi and Kahwa (cuisine unique to the community) line all main streets. Chaush men can be identified by their sartorial choices. They wear geometrically patterned lungis or wraps under kurtas. These wraps are available in shops in Barkas, Lad Bazaar and Shehran. These are popularly referred to as sarung, a word that has etymological roots in Indo-Malay and is now a part of the Arabic language. These are popular items that are bought as gifts by relatives or family when they visit Hyderabad from abroad. It is common knowledge among the Chaush that these sarungs are produced in Malaysia and Indonesia, then supplied to the Gulf, from where they are marketed elsewhere.

Hadrami naming patterns can be witnessed across Chandrayangutta and Barkas

The garment also allows one to locate the Hadrami diaspora in the larger matrix of global capitalist production and supply chains. During the late colonial period, Hadramis in South East Asia, especially Indonesia, acted as intermediaries in the cloth business. The local batik industry there still remains a site from where the sarung cloth is produced. Similarly, the open ‘Arab style’ sandals have become very popular amongst the Chaush community in the last three decades. These are produced in South East Asia and then supplied from Dubai to Yemen and elsewhere in the Indian Ocean region.

For a Chaush, the distinction between Arab and Hadrami identity is blurred – Arab being a meta-identity that subsumes the Hadrami identity. However, Hyderabadi Hadramis primarily associate themselves with the creolised Chaush identity and as Syed/Mashiekh/Qabail – social stratification systems of Hadramawt. Therefore, Chaush identity is truly translocal – diasporic yet stratified on traditional lines. It is regional – Arab and Hadrami at the same time. Most importantly, Chaush identity is also universal – most are members of Shafi’i Maddhab (Sunni sect) yet in Hyderabad it is not uncommon for various Sunni sects to pray together.

Modern Yemeni and Indian nation-states complicate the Chaush identity because the homogenising narratives of these postcolonial nation-states affirm ideas of fixed borders and reified identities. However, for the Chaush, the links with Hadramawt as a geographic entity or a socio-political imaginary allows for demarcation of boundaries of their identity. Yet, state-centric definitions of ‘host society’ and ‘home country’ are too limited to capture or understand these meanings.

Lad Bazaar

The word watan comes closest to the idea of a homeland for the Chaush. Watan does not mean a nation-state, but it is an interplay of translocal geographies of origin/s, that is, regions, cities or villages. For the Chaush, members born in Hadramawt or watan are called Wilayati (literally foreign born; a person born in Hadramawt ‘the homeland’ is still a foreigner to the creole) and those born outside the homeland (diasporic) are called Muwalladin (foreign born creole/of mixed parentage, hence non-pure), denying the possibility of authentic or the stress to retain a ‘pure’ core or a ‘syncretic’ present – in practices, customs, traditions or language. Hadramis born in India are called Mawlluwd-e-Hind. Chaush means both Wilayati as well as Muwallad. A Chaush never belongs.

The movement of the muwalladin as a historic diaspora also gets reflected in the current trends of migrating to the Gulf within the Chaush community in Hyderabad. Post police action, most Chaush found themselves stripped of their normative privileges and status, and ended up participating in the informal sectors of the postcolonial Indian State. Today, the community finds it difficult to compete with those who have more social capital in terms of access and education. Almost all Chaush households have one or more members working in the Gulf. Economic migration to the Gulf began in the 1960s, however, it intensified in the 1970s with relaxed passport and visa regimes.

Migrating to the Gulf is preferable to working in Hyderabad for most Chaush, not only because it offers better economic opportunities, but also because there is a relative ease with the idea of moving within the Indian Ocean area. Therefore, given the high demand for labour in the Gulf markets and the established networks that this community has, it is easier to transcend the disadvantages it faces at ‘home’ by migrating. Interestingly, many Chaush women – young and old – who have not been to newer malls and markets in Hyderabad, know street names and malls in Dubai and Jeddah.

The Chaush identity defies notions of authenticity. This diaspora affirms that a ‘lived everyday’ is located in between historically contingent local/s and universal. For them translocal mobility is normal. It opens up questions regarding different ideas of assimilation and integration that have prevailed in the non-west, specifically in the Indian Ocean region. And offers new frames for understanding concepts like homeland, host society, and notions of belonging.

The point above cannot be emphasised enough in a time when within India, many intellectuals – public and otherwise – are trying to ‘defend’ Indian Muslims by pitting a limited local syncretic South Asian Islam against the universal barbaric global Islam. This practice is not only intellectually dangerous for it presents a part of Indian Muslims identity as its whole, but also because it is laced with the remains of orientalised ideas of Islam. The idea that universal Islam is the other of the modern world has been witnessed in multiple guises since enlightenment – sometimes as racism, sometimes as development and sometimes as a defence of human rights. The work of South Asianists, which implicitly borrows from this dichotomy of a bad revivalist global Muslim versus a Good Indian syncretic Muslim, only reinforced Islamophobic tropes and suspicions against an already vulnerable population. Hence, the Indian Ocean region, Deccan and Hyderabad offer a methodological possibility for us to develop a more inclusive approach to identity formation.

This article was first published in The Newsminute as a part of the Deccan series.

Related Articles

Has Rap Found its Home in the Deccan?

The Deccan is a place of unlikely arrivals and departures – cultural practices from every possible region of the world have found home here and gotten reinterpreted and gifted back to other regions. One such recent arrival is hip hop from Black and Hispanic...

A God, A Pirate and the Birth of a New Urban Religion in the Deccan

Who was Vavar? There are many strands to this story.

The After-Lives of Historical Figures in the ‘Pan-Indian’ Telugu Film

Contemporary film history of the Telugu people has at least one instance of a hyper masculine superhuman celluloid figure that appears time after time to establish territorial order: Alluri Sitarama Raju. The source for this celluloid figure was the leader of what...

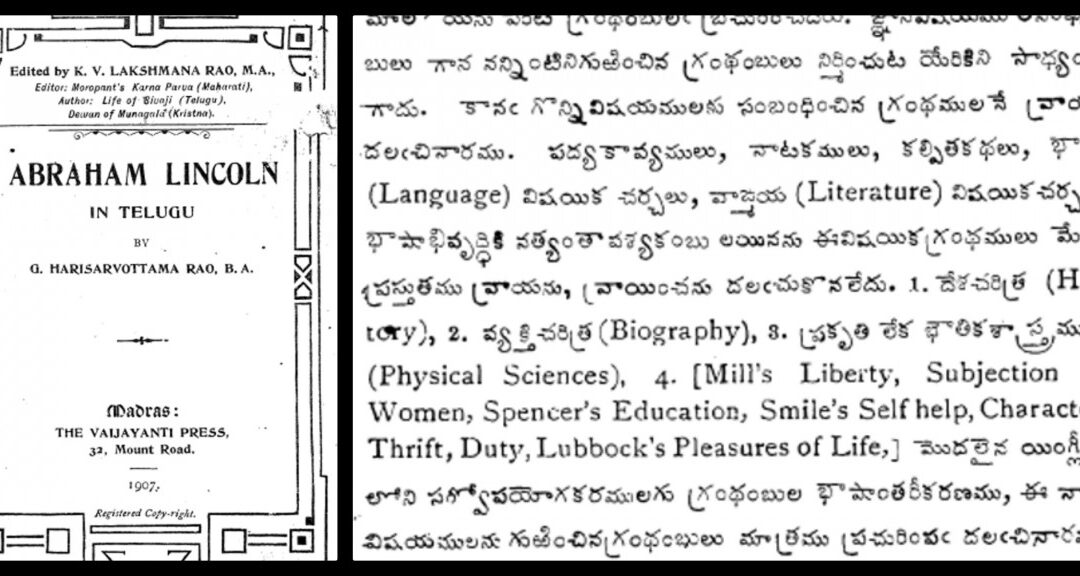

Telugu Modernity and the Curious Case of Enlightened Privilege

In 1907, Vijnana Chandrika Mandali, a Telugu publishing house, began their operations with the goal to ‘improve Telugu literature’.

The Mulki and the Mulk: How Belonging Is Layered in the Deccan

The categories of Mulki and non-Mulki began to appear on the Hyderabadi political scene from the mid-19th century onwards as a response to the influx of Urdu-speaking North Indians being recruited into the state administration.

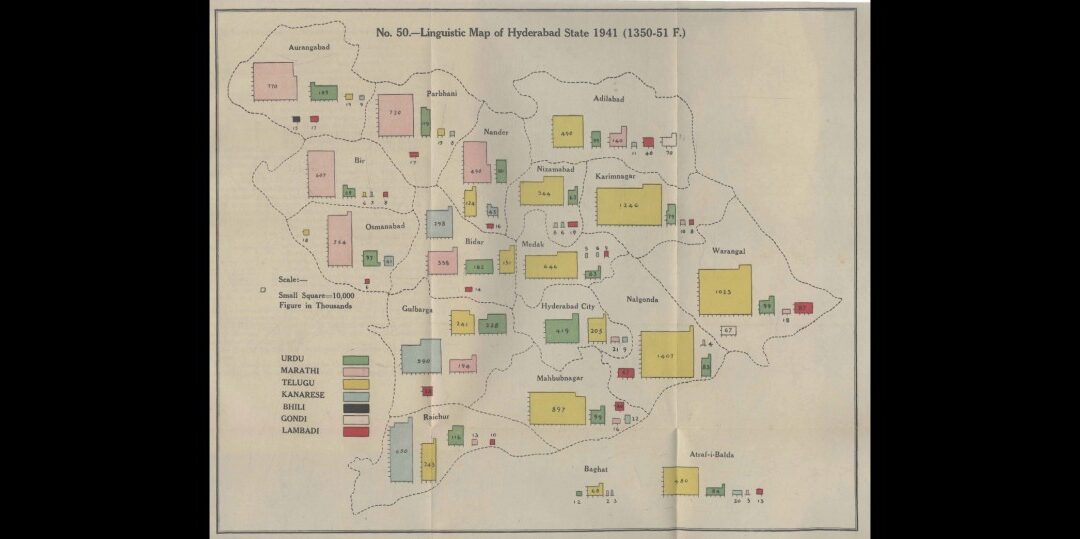

The Uncanny Sisterhood of Deccan’s Languages

‘Pora khaalli? (Have the children eaten?)’ These are two utterances in Marathi spoken in Osmanabad and Solapur districts. But a speaker of Marathi from the central or western parts of Maharashtra may be perplexed at what is being asked of them. Is ‘Kaa karlaalaav’ the...

Deccani Identity: Instrumental Logic or Deep Love of Land?

The diverse ways in which the Deccani identity is invoked in textual sources and oral traditions indicate that newcomers to the Deccan adapted to the ways of the land, developed strong affinities to local landscapes, and adopted cultural practices and markers.

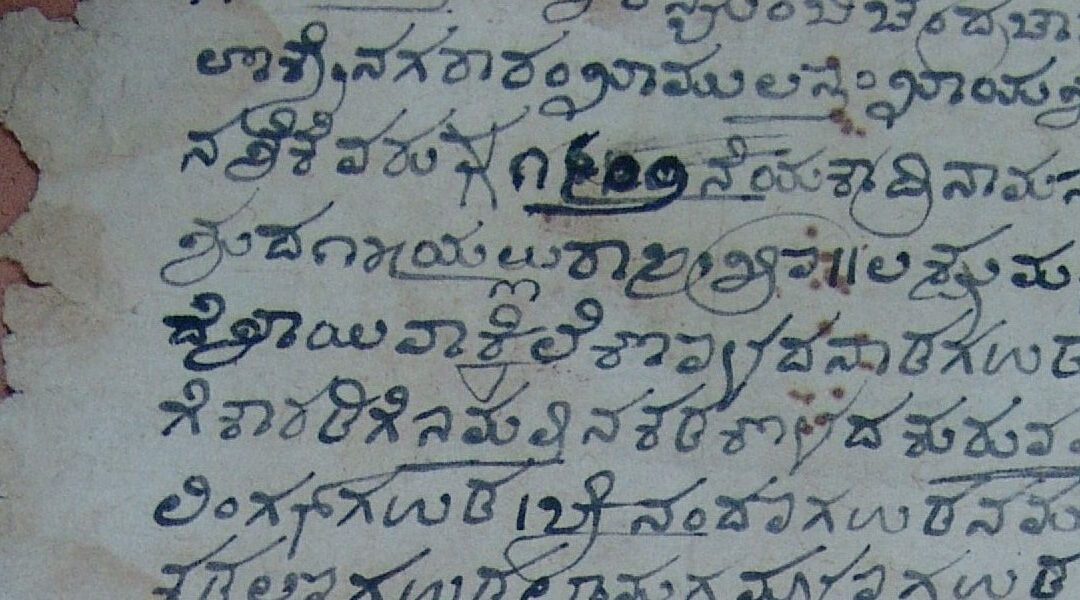

What an 18th-Century Sale Deed Reveals About Language and Territory in the Deccan

The documents hint at more give-and-take in the scribal environment than the one-way “imperial” narrative premised on modern mono-linguistic identities.

Afterword: Who does the Deccan belong to?

On September 17, 1948, more than a year after India became independent, the Hyderabad–Deccan state was integrated into the new Indian nation-state ruled from Delhi. This event, celebrated by some as “liberation,” set in motion decisive processes of integration,...

Rabindranath Tagore’s visit to Hyderabad: When poetry triumphed over politics

The September 17th anniversary of the ‘Police Action’, which led to the integration of the princely state of Hyderabad in 1948, has become increasingly contentious with selective use of history by political parties to further their current polarising agenda. Lost in...