The After-Lives of Historical Figures in the ‘Pan-Indian’ Telugu Film

Contemporary film history of the Telugu people has at least one instance of a hyper masculine superhuman celluloid figure that appears time after time to establish territorial order: Alluri Sitarama Raju.

The source for this celluloid figure was the leader of what came to be known as the Rampa rebellion of tribals against the British in 1922, in the Madras Presidency districts. Alluri Sitarama Raju, a local kshatriya youth of 20 odd years and inclined towards austerity and cultivation of spiritual goals, organised the tribals to raid the local British police stations in the forest settlements. Although initially Alluri struck fear in the British authorities by guerilla tactics, gradually the British managed to gain an upper hand by moving in army units and capturing and killing him and his associates in 1924.

This rebellion led by Alluri was only one of the many tribal rebellions. While most tribal leaders are forgotten, Telugu films have reminded us of Alluri time and again. In the latest incarnation, Alluri appears to serve the call of Hindutva. In April 2022, a district in Andhra Pradesh state was named after Alluri. More recently, Prime Minister Narendra Modi inaugurated the 30-feet statue of Alluri set up by Kshatriya Seva Samiti in West Godavari district on July 6, as a part of the BJP’s outreach to both the tribals and the Raju community.

The figure of Alluri Sitaramaraju has evolved over the last one hundred years into its contemporary version – an intertwining of masculinity, caste, religion and language. In the 1974 film Alluri Sitarama Raju, the title role was played by Telugu star Krishna. The film begins with a song which places the Rampa tribal rebellion led by Alluri along with the Rani of Jhansi, the revolt of 1857 and Jallianwala Bagh massacre of 1919. A seamless nationalist narrative is created.

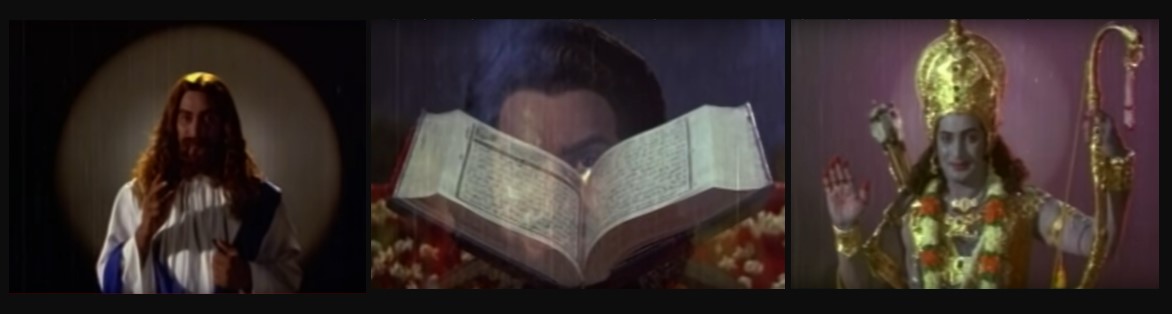

At this point, although we see the hero Krishna as Alluri donning saffron on and off in the film, these are without any explicit Hindu assertions. He may pray to the goddess Kali but the film is clear that the hero’s commitment is to rebellion rather than to Hinduism. When a British official orders the soldiers to shoot him, the Hindu soldiers see a Hindu god in him, the Christian soldiers see Jesus in him and the Muslim soldiers see the Quran, and they all refuse to shoot. He is finally shot by a British official.

Krishna as Alluri Sitarama Raju in the 1974 film.

This representation of Alluri as a ‘Telugu’ hero came in the context of many socio-political changes in the Telugu sphere broadly and in the film industry, particularly. From the 1940s onwards, writers and intellectuals such as Kodavati Kutumbarao started speaking about ‘nativity’ and representing nativeness or ‘Teluguness’ on screen. As the linguistic identity movement was gaining force, Telugu cinema had to be differentiated from other south Indian cinemas through this Teluguness. The site of Teluguness was imagined to be the coastal Andhra village with paddy fields and women in traditional attire on screen. The Teluguness here meant the representation of the peasant capital of Kamma castes on screen. The 1974 Alluri Sitarama Raju film came after the first movement for a separate Telangana in 1969. This demand for a separate state called for a reinvigoration of the Telugu identity. This context is reflected in the film and we see Alluri Sitarama Raju presented as a ‘Telugu’ hero. The prominent song on Alluri in the 1974 film, ‘Telugu veera levara’ was written by Sri Sri, a member of the Revolutionary Writers’ Association.

Telugu veera levara

Deeksha buni sagara

Desha mata sweccha kori

Tirugubatu cheyara

(Awaken O Telugu hero

Take a pledge and go ahead

for the freedom of the mother nation

rebel)

Funded by Kamma capitalist Krishna, the film drew a direct relationship between Telugu identity and the national identity. The rebellion against the British was a ‘Telugu’ contribution to the nation.

The second representation of Alluri appears in the song ‘Punyabhoomi Nadesam’ in the N.T. Rama Rao starrer Major Chandrakanth, a 1993 film. This song comes as an interlude when an army major is schooling his grandchildren on patriotism. In this song Alluri is placed among other martyrs of the nation such as Chhatrapati Shivaji, Veerapandiya Kattabomman and Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose. The film is entirely built on the idea of sacrificial sons for mother India and narrates the story of an army Major and his societal contributions.

In this song, we see a communal re-interpretation of history. For instance in this film which was released in a post-Babri India, Shivaji is presented as fighting against communal forces (while calling them communal forces, the film alluded to Muslims) who were violating Indian women. Here we see a placeholder for the sacrificial national hero and the nation’s enemy created; all stories be it across different historical times, contexts were told through these templates. The Alluri section of the song shows a hundred cannons being fired at once to kill him with the skies crying out Vandemataram.

The song in many ways reflects the politics of N.T. Rama Rao. In his political career, this film came in between his two terms as chief minister (In office: 1983-84; 1984-89; 1994-95). The Telugu identity of N.T.R was intertwined with an ascetic Hindu identity. He donned saffron in his electoral campaign and appealed to the Hindu sensibilities, even though he was outside the BJP. The Hindu-Telugu identity was cemented by N.T.R.

He won the elections and became the chief minister by pitching the distinctiveness of Teluguness as an electoral platform by suggesting that the Telugu pride was being subjugated by the national. In an attempt to set up the pantheon for Telugu identity and Hyderabad, Alluri Sitarama Raju statue was set up on tank bund along with others such as Gurajada Apparao, Suravaram Pratapareddy, Ballari Raghava, Maqdoom Mohiuddin etc. by N.T.R.

Ram Charan as the muscular Alluri wearing a janeu in RRR.

In the third and latest iteration, Sitarama Raju appears alongside Komaram Bheem, a tribal rebel from what is now Telangana, in the ‘pan Indian’ 2022 film RRR. In the film, a police officer working for the British has the name Alluri Sitarama Raju. Though the film actually does not represent the historical figure, it constantly alludes to him. The song ‘Ramam Raghavam’ focused on Alluri figure is an interesting mix of Sanskrit-sounding words set against guitars and drums. More importantly, the song has an entire choir dressed in saffron-coloured clothing along with the hero himself.

In this film, the figure of Alluri played by the hero Ram Charan is constantly pitted alongside the figure of Komaram Bheem, played by junior N.T. Rama Rao. The connection drawn through the comradeship between the Raju of the coastal Andhra and the gond of the north Telangana is noteworthy as it comes less than a decade after the two states are separated. Similar to Alluri, the figure of Komaram Bheem also has contemporary significance in popular Telangana imagination. Bheem has been resurrected during the Telangana struggle and the need for recovering forgotten local histories. A district in Telangana was named after Komaram Bheem in 2016.

Our latest incarnation of Alluri is a chiselled, muscular figure, akin to the muscular Hanuman which is ubiquitous now. Unlike the 1974 film, the 2022 film prominently represents the sacred thread (janeu), indicating the upper caste status of Alluri Sitarama Raju. If there was any doubt in the affiliations of this new hero, it is cleared in the YouTube comments section for the song. Many comments make reference to ‘Sanatana Dharma’, often ending with ‘Jai Sri Ram’, ‘Proud to be a Hindu, proud to be an Indian’. Here, Alluri Sitarama Raju becomes conflated with the mythological figure of Ram. This mythologisation of historical figures is similar to what is seen in Amar Chitra Katha comics which reinforce the tenets of Hindu nationalism.

The singing crew in the ‘Ramam Raghavam’ song from RRR.

The main point to be considered here is that Alluri as a representative of Andhra Pradesh and Komaram Bheem of Telangana are both aligned seamlessly with the rise of global Hindutva. It is a Hindutva that imagines the Hindu male as a virulent super hero whose masculinity is on constant display. The upper-caste, super-human, male hero is common across most Telugu films, as seen in films like Samarasimha Reddy, Indra etc. These films are dubbed into Hindi and are distributed widely through Hindi film channels and they can be considered as precedents to the ‘pan-Indian’ Telugu film. They have built a taste for the Telugu films in north Indian markets.

In the ‘pan-Indian’ Telugu film, this Telugu hero template is presented as a type – mythical Hindu male, a tribal man or a mafia leader, in order to be intelligible to ‘pan-Indian’ audience. The British villains become another narrative ploy to create a ‘national’ appeal. This, of course, completely bypasses the historical fact that the experience of British colonialism itself was not uniform across the subcontinent. This replicable model is attempted in Hindi films like Shamshera, Bramhastra etc. Another ‘pan Indian’ Telugu film ‘Liger’ makes a direct reference to Prime Minister Modi by the use of the term ‘Chai Wala’ thereby directly making its affiliation visible.

From 1974 to 2022, we see a shift in the representation of the historical figure of Alluri towards becoming a mythological figure akin to Ram, situated in mythologized geographies, ahistorically and even fantastically. The history of ‘pan-Indian’ Telugu film marks the move from intertwining of Telugu-Hindu identity to a complete subsumption of the Telugu into Hindu and the mythological.

While the other essays in this series ‘Many worlds of the Deccan’ have shown us how diverse practices mark the Deccan, it is also important to document the political projects – in this case the popular film – which lends force to the homogenising, national, Hindu and linguistic identities. This essay illustrates how a majoritarian Telugu identity crafted in films through the period starting from the 1950s is giving way to the Hindu identity.

This article first appeared in The Wire as part of the Many Worlds of the Deccan.

Related Articles

Has Rap Found its Home in the Deccan?

The Deccan is a place of unlikely arrivals and departures – cultural practices from every possible region of the world have found home here and gotten reinterpreted and gifted back to other regions. One such recent arrival is hip hop from Black and Hispanic...

A God, A Pirate and the Birth of a New Urban Religion in the Deccan

Who was Vavar? There are many strands to this story.

Telugu Modernity and the Curious Case of Enlightened Privilege

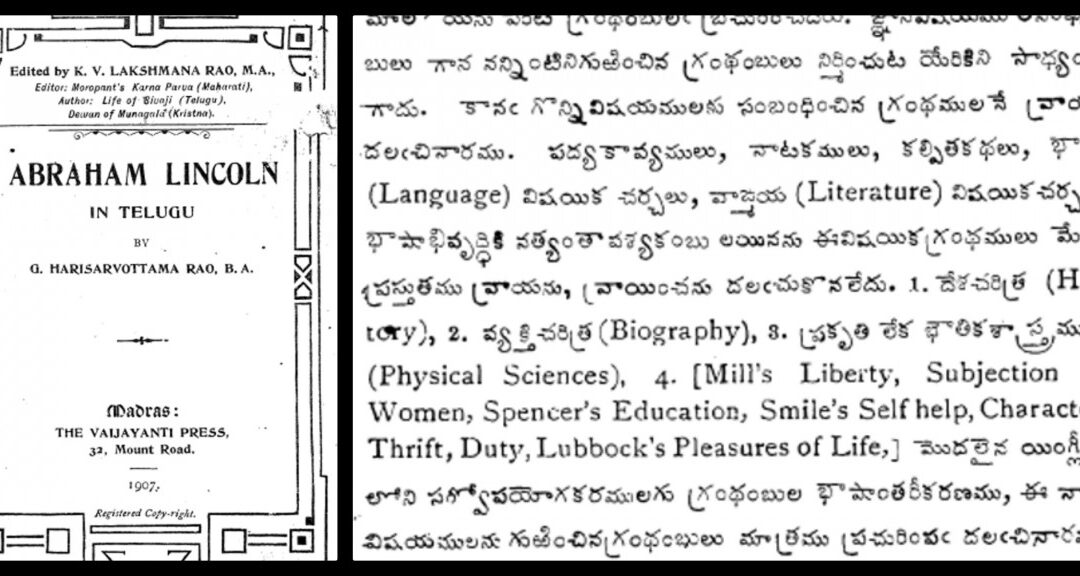

In 1907, Vijnana Chandrika Mandali, a Telugu publishing house, began their operations with the goal to ‘improve Telugu literature’.

The Mulki and the Mulk: How Belonging Is Layered in the Deccan

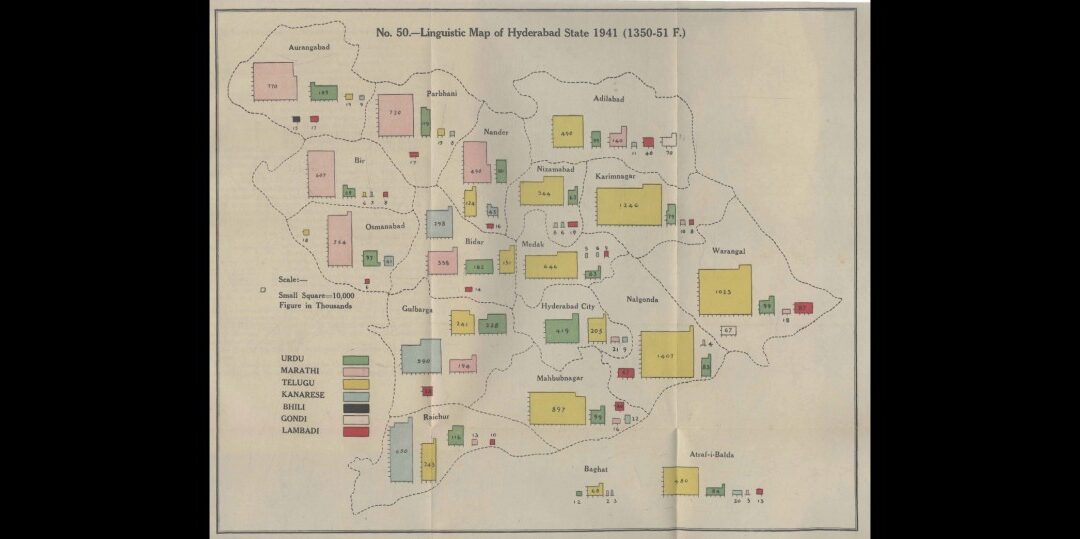

The categories of Mulki and non-Mulki began to appear on the Hyderabadi political scene from the mid-19th century onwards as a response to the influx of Urdu-speaking North Indians being recruited into the state administration.

The Uncanny Sisterhood of Deccan’s Languages

‘Pora khaalli? (Have the children eaten?)’ These are two utterances in Marathi spoken in Osmanabad and Solapur districts. But a speaker of Marathi from the central or western parts of Maharashtra may be perplexed at what is being asked of them. Is ‘Kaa karlaalaav’ the...

Deccani Identity: Instrumental Logic or Deep Love of Land?

The diverse ways in which the Deccani identity is invoked in textual sources and oral traditions indicate that newcomers to the Deccan adapted to the ways of the land, developed strong affinities to local landscapes, and adopted cultural practices and markers.

What an 18th-Century Sale Deed Reveals About Language and Territory in the Deccan

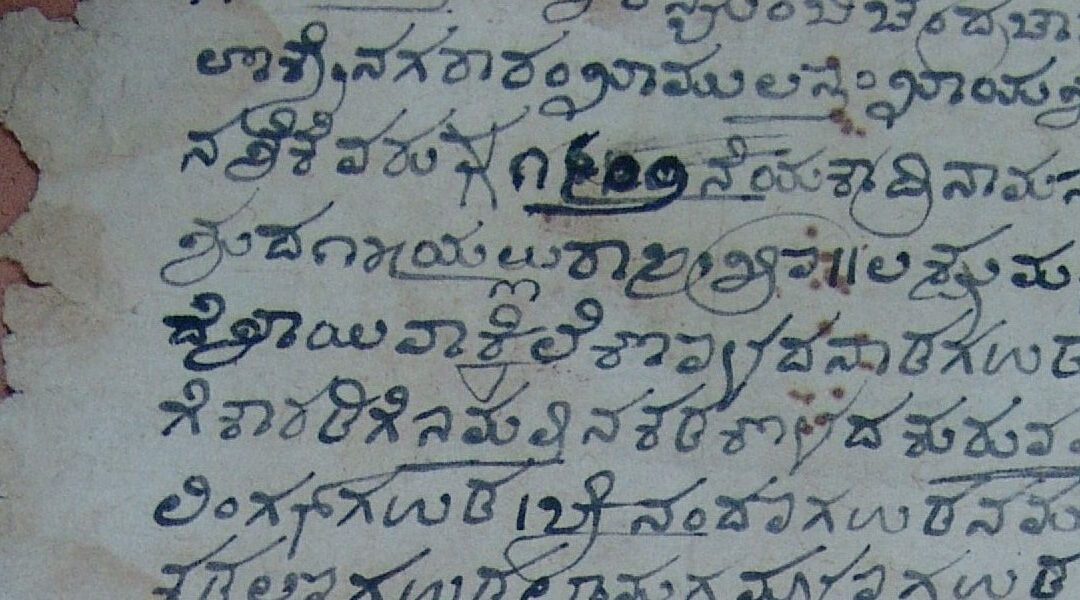

The documents hint at more give-and-take in the scribal environment than the one-way “imperial” narrative premised on modern mono-linguistic identities.

Afterword: Who does the Deccan belong to?

On September 17, 1948, more than a year after India became independent, the Hyderabad–Deccan state was integrated into the new Indian nation-state ruled from Delhi. This event, celebrated by some as “liberation,” set in motion decisive processes of integration,...

Rabindranath Tagore’s visit to Hyderabad: When poetry triumphed over politics

The September 17th anniversary of the ‘Police Action’, which led to the integration of the princely state of Hyderabad in 1948, has become increasingly contentious with selective use of history by political parties to further their current polarising agenda. Lost in...

Hyderabad’s distinct Chaush community has roots in Yemen

At a time when Muslims in India are constantly asked to display their nationalism and explain their choices of food, love and profession, it is important to remember that identity is not a monolith. It is historically constructed and multidimensional. Neither can it...