What the Hyderabad-Deccan region teaches us about belonging

During fieldwork for my PhD on Hyderabad-Karnataka in the year 2017, I was interviewing women migrants from the region living in Bengaluru and working as construction labour, about their experience of migration. The region is one of the most neglected parts of Karnataka and in popular narratives, its poverty is blamed — wrongly — on its having been part of the Nizam state. Since the 1980s, there has been a steady distress migration from the region to Bengaluru. The women recounted their helplessness in the initial years in Bengaluru when they could not understand the local Kannada dialect at all.

“We would just stare at people blankly if they spoke to us. We didn’t understand what they said and they would not understand what we said,” one woman told me. To them, the fact of belonging to a linguistic state had offered no comfort in times of their distress migration. What did offer them some comfort was a sense of community they felt staying together with other migrants from the region. Together, they shared a belonging to the desha, a space of familiarity where individuals shared common practices of language, food and living.

Over long years of residence in the city and the continuous circular migration between the region and the city, Bengaluru had to some extent become part of the desha for the women I interviewed. But these belongings remained unrecognised by the state for whom the migrant had to always return to her proper space of belonging — the village — after she served the city with her labour. In the dominant worldview of states and its ideologues, one can belong to only one space — to one nation, to one linguistic community, to the village your husband hails from.

This idea that we can belong to only one entity has also shaped contemporary history and politics in the Deccan.

Territorial formations in the Deccan

On September 17, 1948, Hyderabad-Deccan ceased to exist as a princely state and was annexed to the newly formed Indian Union through an Indian Army operation termed ‘Police Action’. On this day, the last Nizam of the Asaf Jahi dynasty, Mir Osman Ali Khan, gave up his claim to retain the state as an independent unit which was not aligned to Pakistan or India.

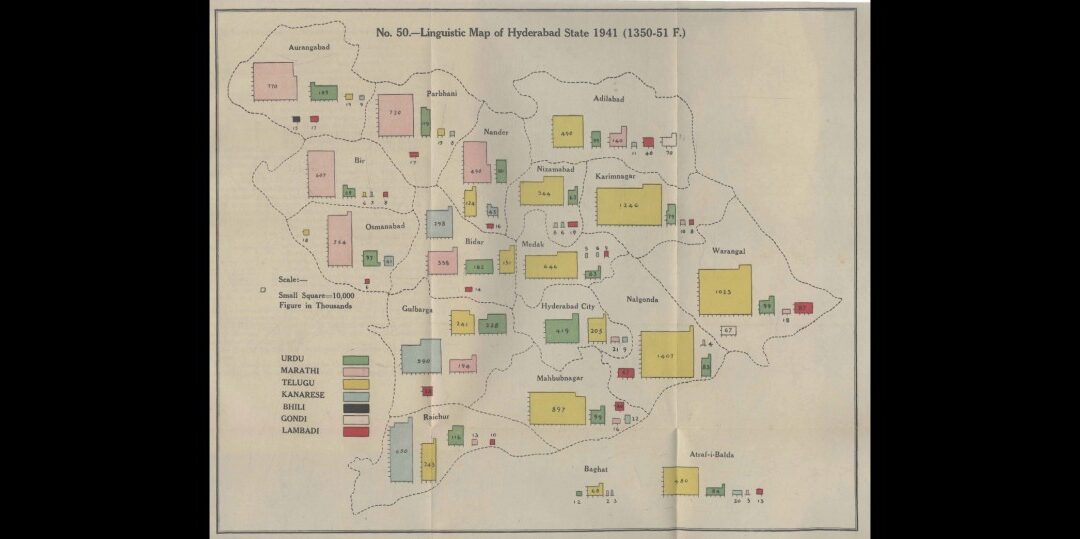

Years later, on November 1, 1956, the Hyderabad-Deccan state itself ceased to exist as its constituent parts of Hyderabad-Karnataka, Telangana and Marathwada were joined into the linguistic states of Mysore (now Karnataka), Andhra Pradesh and Maharashtra (then called Bombay state until 1960). In June 2014, the Telangana districts of the erstwhile Hyderabad-Deccan state were separated from Andhra Pradesh state to form a new state.

On September 17, 2019, to mark what is now being called ‘Hyderabad Liberation Day’, the-then Karnataka Chief Minister BS Yediyurappa renamed the Hyderabad-Karnataka region as Kalyana-Karnataka. This was both a promise that ‘kalyana’ (progress) will be brought into this neglected region and a nod to the political predominance of the Lingayat faith for whom the place Kalyani (now called Basavakalyan in Bidar district) holds an important place in its history.

Each of these events speak of how ideas of territorial belonging take on a political form. If the annexation of Hyderabad was the fruition of a dominant sentiment that Hyderabad-Deccan belongs properly to India alone, the disintegration of the state was an assertion that different linguistic regions do not belong with each other but with their linguistic counterparts neighbouring them. The separation of Telangana was an assertion of the distinctiveness of the region while Yediyurappa’s renaming of Hyderabad-Karnataka can be read as an attempt to erase the region’s connection to Hyderabad state and yoke it to the dominant caste community that has been his loyal support base.

Hyderabad and India

In a White Paper on Hyderabad in 1948, the Indian government claimed that there had been a ‘complete collapse of law and order in the state’ and that the majority community was being harmed and that Razakars had taken to looting, arson and violence. Although new archival material has called into question this narrative of widespread violence, the narrative has sustained over the years in public imagination. The calls to term this day as ‘liberation day’ is a provocative amplification of this narrative.

The Indian Union’s actions at that time were justified by vocal demands by non-state actors such as the Hyderabad State Congress (HSC) and the Arya Samaj among others. The premise was that the only right form of belonging for everyone, particularly the state’s majority Hindu subjects, was to the Indian nation.

However until about 1946, even the HSC and the Arya Samaj, were not demanding that the Nizam be overthrown or replaced. Rather, their demand was for representative institutions to share state power with the Nizam. It is only when political processes in British India began to give concrete shape to the idea of an independent Indian state that allegiances were shifted to the new nation to come.

These details are important because it alerts us to a time when neither the shape and form of the Indian nation nor the relationship of various territorial entities (which we now call as federal states) to the Union was settled. Belonging to the Indian Union was not imperative; in the 1940s, it was still evolving, being negotiated and had to contend with other assertions of belonging.

Hyderabad and its disintegration

In the early 1950s, the demand for linguistic reorganisation of states began to grow in south India. Key to this reorganisation was the disintegration of Hyderabad. Claims were made that the state was an ‘unnatural entity’ because four dominant linguistic communities had been ‘forced’ to stay under a ‘feudal’ ruler.

The movement for linguistic reorganisation was based on the premise that a linguistic community needed to belong to a territorial unit where its language was predominant. Within this world-view where an individual is considered as belonging to only one linguistic cosmos, the existence of Hyderabad itself was considered offensive.

Again, it is useful to remember that these were just one of the many visions in the 1950s. For example, when talks of disintegration of the state were afoot, even Pandit Narendra of the Arya Samaj and later Congress, who had been a vocal critic of the Asaf Jahi dynasty opposed it. He argued that there was no large-scale support for the disintegration of the state; if the state was ‘unnatural’ because it was multilingual, then the same could be said of India where at least 52 languages were being spoken. For him there were no correct or unilinear forms of belonging. Diversities and multiplicities could co-exist and were not threatening to one another.

As events played out in Hyderabad-Deccan, these different visions of belonging circulating in the 1940s and 50s in and about the region may have died. But the women like those I interviewed during my fieldwork create and live in multiple spaces and times to which they feel a sense of belonging. They defy territory. These belongings are often physically and emotionally more enduring than the nation or the linguistic state. These are the anchors of community.

This article was first published in The Newsminute as a part of the Deccan Series.

Related Articles

Has Rap Found its Home in the Deccan?

The Deccan is a place of unlikely arrivals and departures – cultural practices from every possible region of the world have found home here and gotten reinterpreted and gifted back to other regions. One such recent arrival is hip hop from Black and Hispanic...

A God, A Pirate and the Birth of a New Urban Religion in the Deccan

Who was Vavar? There are many strands to this story.

The After-Lives of Historical Figures in the ‘Pan-Indian’ Telugu Film

Contemporary film history of the Telugu people has at least one instance of a hyper masculine superhuman celluloid figure that appears time after time to establish territorial order: Alluri Sitarama Raju. The source for this celluloid figure was the leader of what...

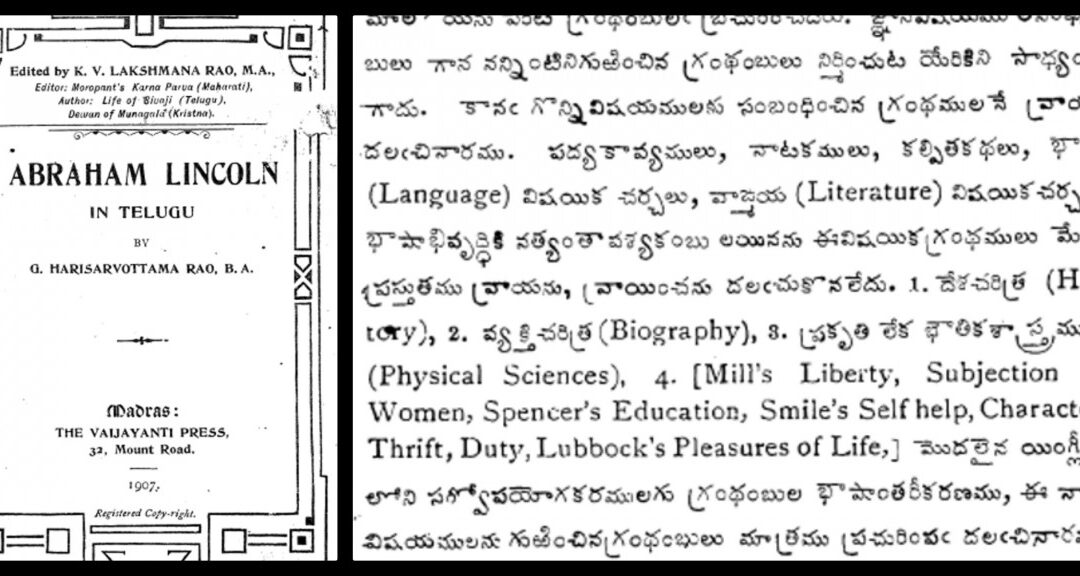

Telugu Modernity and the Curious Case of Enlightened Privilege

In 1907, Vijnana Chandrika Mandali, a Telugu publishing house, began their operations with the goal to ‘improve Telugu literature’.

The Mulki and the Mulk: How Belonging Is Layered in the Deccan

The categories of Mulki and non-Mulki began to appear on the Hyderabadi political scene from the mid-19th century onwards as a response to the influx of Urdu-speaking North Indians being recruited into the state administration.

The Uncanny Sisterhood of Deccan’s Languages

‘Pora khaalli? (Have the children eaten?)’ These are two utterances in Marathi spoken in Osmanabad and Solapur districts. But a speaker of Marathi from the central or western parts of Maharashtra may be perplexed at what is being asked of them. Is ‘Kaa karlaalaav’ the...

Deccani Identity: Instrumental Logic or Deep Love of Land?

The diverse ways in which the Deccani identity is invoked in textual sources and oral traditions indicate that newcomers to the Deccan adapted to the ways of the land, developed strong affinities to local landscapes, and adopted cultural practices and markers.

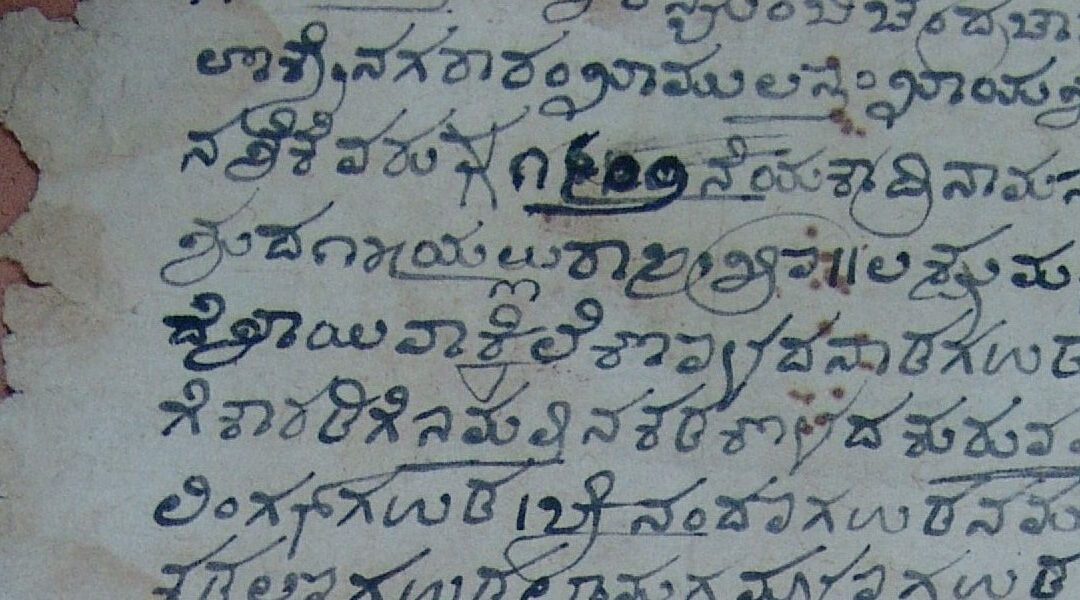

What an 18th-Century Sale Deed Reveals About Language and Territory in the Deccan

The documents hint at more give-and-take in the scribal environment than the one-way “imperial” narrative premised on modern mono-linguistic identities.

Afterword: Who does the Deccan belong to?

On September 17, 1948, more than a year after India became independent, the Hyderabad–Deccan state was integrated into the new Indian nation-state ruled from Delhi. This event, celebrated by some as “liberation,” set in motion decisive processes of integration,...

Rabindranath Tagore’s visit to Hyderabad: When poetry triumphed over politics

The September 17th anniversary of the ‘Police Action’, which led to the integration of the princely state of Hyderabad in 1948, has become increasingly contentious with selective use of history by political parties to further their current polarising agenda. Lost in...