Telugu Modernity and the Curious Case of Enlightened Privilege

The turn of the 20th century was an enormously productive period in publishing in Indian languages. Although prose publication for non-scholarly readers began as early as 1875, closely followed by the adoption of the novel as a form of writing, large-scale printing and distribution efforts did not take off until the 1890s. Debates raged on the virtues of formal writing styles versus adoption of spoken language forms for writing.

This was a period when enlightenment ideals of equality and liberty were seizing the minds and hearts of the colonial subjects. While their aspirational goals were equality and liberty through literary production for a regional readership, the path towards those goals were thwarted as material resources were hopelessly entangled in processes that pulled in the opposite direction. In what follows, I tell the story of one such effort that took place more than a century ago which may hold lessons for contemporary regional literary efforts.

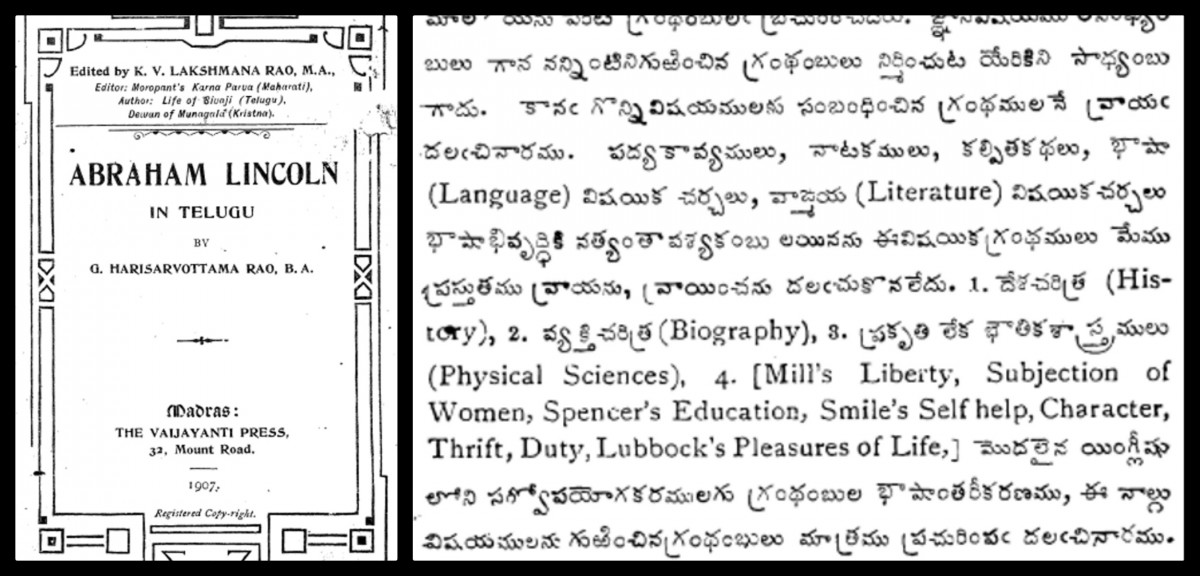

In 1907, Vijnana Chandrika Mandali, a Telugu publishing house, began their operations from the residency bazar in Hyderabad. In 1908, it shifted its operations to Madras and continued to function from there. Their first offering while they were still located in Hyderabad was a Telugu biography of Abraham Lincoln. In this biography, the Mandali published a founding document – a sort of a manifesto of the publishing house. The publishers announce in this document their intention to launch what may in retrospect be described as a vernacular literary modernisation project through the publication of translated works of western knowledge – the likes of Lincoln’s On Liberty. Some of the key points in this manifesto alluded to equipping vernacular languages with the vocabulary required to translate western knowledge, and publishing science and history books in Telugu. In the words of the editors, ‘Improvement of Telugu Literature’ was the goal.

The first signatory of the founding document was Nayani Venkata Ranga Rao, the zamindar of Munagala Paragana (now located in the Suryapet district of Telangana state). He was one of the founding members and patrons of the society and donated the founding capital required to start the publishing house. The chief editor was Komarraju Venkata Lakshmana Rao, the diwan of Munagala Zamindari. The other members were Ayyadevara Kaleswara Rao (freedom fighter and advocate for public libraries), Achanta Lakshmipathi (writer and scholar of ayurvedic system of medicine), Ravichettu Ranga Rao (founder of many libraries and educationist) and Gadicherla Harisarvothama Rao (founder of the public library movement in the Telugu speaking regions).

An excerpt from the founding document of the Mandali where they list out the genres and books that they plan to publish in Telugu. Courtesy: National Digital Library of India

This was effectively a gathering of Brahmins and landed Shudra castes who collaborated with each other to establish institutions like Srikrishna Deva Ray Andhra Bhasha Nilayam – a library that still serves readers of Hyderabad, among other institutions. The founding document states that their only interest in this project was to add to the corpus of modern Telugu literature by venturing into hitherto unpublished genres and that they were not expecting any monetary returns.

At the turn of the 20th century, the patronage structures of Telugu literature were changing. While earlier it was the royal patron who would exclusively fund literary work, now there was an evolving sense of market orientation and publishers were trying new business models and appealing to a fledgling Telugu reading public. In fact, the founding document uses the word ‘Telugu Reading Public’ to refer to its readers. Publishing houses like the Mandali were eventually registered as joint stock companies or literary associations and they maintained clear balance sheets, profit and loss statements. But this was an evolving market and they still needed the support of the earlier patronage networks for funding.

The Mandali in the founding document invokes the kings Raja Narendra Eastern Chalukya king of 11th century), Manumasiddhi (Nellore Choda of 13th century) and Krishnadeva Raya (Vijayanagara emperor of 16th century), who were all known to be generous patrons of arts and literature while requesting the aristocratic classes of the time to encourage their efforts financially. Setting up these kings of yore as models, it urges the contemporary aristocracy to encourage creation of literature. This hybrid business model of the Mandali – zamindari patronage and subscriptions by ordinary buyers of books – must be understood in the context of larger transitions that were taking place in the field of cultural production during the period. The consistent patronage received by a few of these publishing houses enabled them to keep functioning even in adversity. For instance, the editor of the Mandali in the preface of a book published during World War I states that although they were finding it extremely difficult to find paper at affordable prices, they were going ahead and printing it despite losses, since their intention was never to make profits but to improve Telugu literature.

The cover page of the first book by the Mandali in which the founding document was published. Courtesy: National Digital Library of India

So, who was this zamindar on whose generosity the Telugu enlightenment project hinged? If we go by accounts favourable to Vijnana Chandrika, Nayani Venkata Ranga Rao, the Munagala zamindar was a benevolent patron of the arts. But other contemporary accounts show him to be an autocratic zamindar ruthlessly exploiting marginal farmers and agricultural labour. Peasant rebellions, like the Munagala Kisan Agitation of the 1930s, were also mobilised against these atrocities. Devulapalli Venkateshwara Rao, a member of the then-undivided Communist Party of India, who led the kisan agitations of the time discusses the philanthropic, arts patronising, well-educated image of the Munagala zamindar and contrasts it with the poor state of the farmers of the pargana under his rule. Reportedly, there were several court cases which challenged the Zamindar’s inheritance and fighting these cases led to the emptying of his coffers, and he in turn was using exploitative means against oppressed-caste farmers in the form of taxation and demanding free labour from them.

The West Krishna District Congress Committee’s 1938 report on Munagala describes the suffering of farmers in detail. In the Nizam state, vetti (vetti begar a state sanctioned system of unpaid labour turned into vetti an entitlement of individuals and families to extract unpaid labour, material and services) and bhagela – two forms of extraction of free labour, services and supplies from the population – were prevalent.

In the vetti system, payments for labour, services and supplies extracted ranged from zero to marginal. The exploiter could be anyone with some form of association with caste or state authority. The exploited likewise could be anyone belonging to a wide range of population groups who were considered subjects of this authority. The rights of the exploiter were considered to have been derived by birth from their forefathers. For example, under vetti, washermen were expected to provide services, traders were expected to provide materials, workers were supposed to work all for free or for a small payment.

Under the bhagela system, individuals sold themselves or their family members into bonded labour until a loan is repaid. The loan records were never written down on paper. Protests were met with severe punishment, which included imposition of fines and torture. Even repairing one’s own property needed the Zamindar’s permission which was granted only after making an adequate payment. The Zamindar also charged his tenants high rent, claimed jurisdiction over grazing lands and evicted tenants without adequate cause.

This material context – of wealth and privilege extracted and defended through extortion and violence – was then the seed bed in which the Telugu enlightenment was germinating. The literary modernity project of the Mandali was inspired by western modernity. Modernity has its origins in the ideas of the Enlightenment in the West and one major emphasis there was on the rights of common people. But in the Telugu literary cosmos, the parties that funded this project were directly involved in exploitation and maintenance of the status quo even as the literary modernity project was meant to challenge it. In a recent (2017) essay titled ‘Ingitham Marchipoyina Rajavaru’ (The King who forgot basic manners/common sense) Gudipudi Subba Rao who authored a local history of the Munagala Paragana criticises the members of the Mandali who lived in close proximity to the Zamindar for ignoring these atrocities and their consequences. Although he does not allude to these histories, a contemporary literary figure the Telugu poet-playwright Gurajada Venkata Appa Rao did take note of how the modernist project of the Mandali was at heart a conservative and reactionary project. He criticises one of the historical novels published by the Mandali saying that it was a ‘violence to common sense’ and that the novelist indulges in describing an ‘imaginary patriotism’.

That the Mandali mentions their wish to translate Mill’s On Liberty into Telugu is not merely ironical. It is an irony that sits at the heart of the project of Telugu literary modernity – where two contradictory aspirations – one to consolidate caste privilege and money power and the other to launch a dream of universal equality and liberty had to compromise with each other. Such is the story of regional literary productions in the Deccan region.

This article first appeared in The Wire as part of the Many Worlds of the Deccan.

Related Articles

How the Dakhni language defines cultural intimacy and regional belonging

In mid-2019, I embarked on a month-long language homestay program in Jaipur to train myself in spoken and written Hindi. After which, I confidently journeyed to Hyderabad to commence my fieldwork for my PhD dissertation in anthropology. To my dismay, I found it...

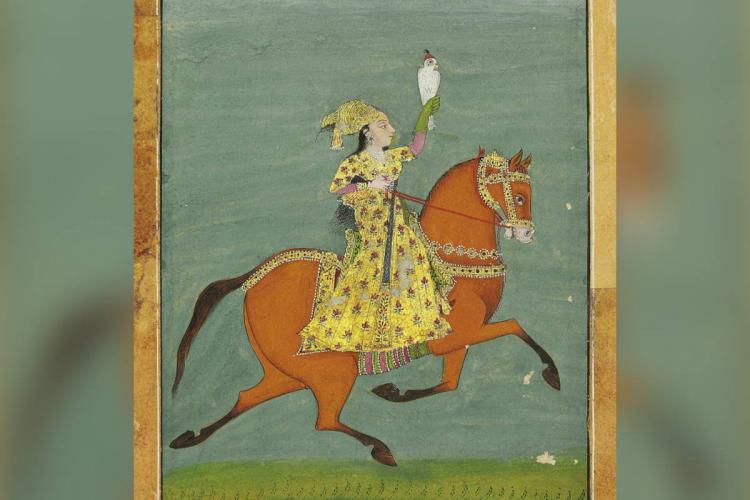

Chand Bibi, a queen from the multi-ethnic medieval Deccan

Where in the historical record and in historical consciousness does Chand Bibi (1550-1600) – the queen regent of Bijapur and Ahmadnagar – belong? Chand Bibi Sultan is well-known in India for valiantly defending her natal kingdom of Ahmadnagar in 1595, from the most...

Becoming a Deccani artist: Tracing the history of Hyderabad’s School of Art and Crafts

In the 1930s and 40s, debates on education across India focused on designing job and industry-oriented technical and vocational training. Against this backdrop, Hyderabad nurtured a second focus — that of preserving and promoting its artistic heritage from ancient...

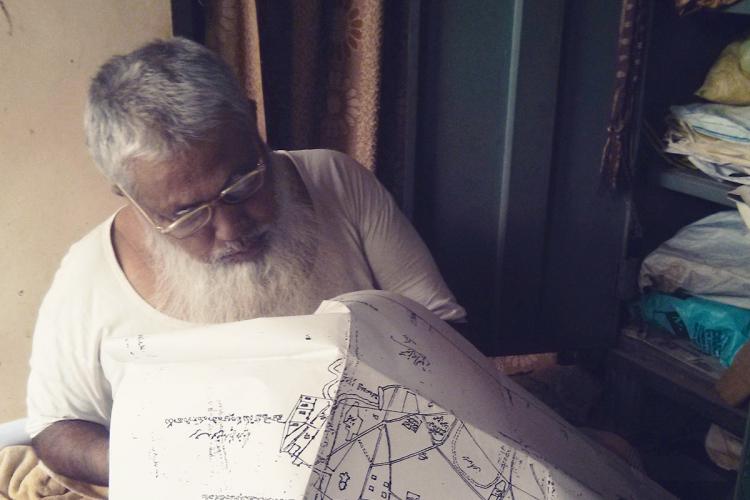

Search for the past: Stories from the dusty archives of the Deccan

As I sifted through some administrative reports of the Asaf Jahi state at the Telangana State Archives in Hyderabad, the archivist/official, a very patient man, sat there trying to match the details written on a small piece of white paper with the endless lists from a...

What the Hyderabad-Deccan region teaches us about belonging

During fieldwork for my PhD on Hyderabad-Karnataka in the year 2017, I was interviewing women migrants from the region living in Bengaluru and working as construction labour, about their experience of migration. The region is one of the most neglected parts of...